November 2004 – Production of this issue sponsored by Bennetts (Irongate) Ltd

Some Parwich Memories

Notes of a phone conversation between Stephen Halliday and Gill Radcliffe

Whilst checking some facts in the final draft of ‘Voices: Women of a White Peak Village’ Gill Radcliffe had a fascinating conversation with Stephen Halliday, son of Edward Halliday. The Hallidays lived at the Fold in the 1930s as tenants of Sir John Crompton-Inglefield. Edward Halliday was active in the local Home Guard, but is best known outside Parwich as an artist. The drawing of Victor Allsop in the Memorial Hall is his work. It was too late to add these notes to her book, so we have included them here. Given the art component to our Celebration of Rural Life & Landscape it is particularly timely to report on Parwich’s most famous artist. Ed.

The Home Guard was first called L.D.V: Local Defense Volunteers. They had no uniforms but wore armbands with L.D.V. on them. They were very Dad’s Army, drilling with their old shotguns slung onto their shoulders by a piece of cord. They acquired an old black horse- drawn caravan which they towed up the back lanes and set up by the wood on Parwich Hill, from where they could man a lookout and be on the alert for paratroopers. It sounds funny now but at the time it was deadly serious! I think Winston Churchill renamed them the Home Guard. Eventually they were issued with uniforms and World War I Rifles. I remember the uniforms arriving and the men trying them on in my father’s studio at the Fold, and one man pulling on a pair of trousers and saying “Eee, there’s room for anoth’un in ‘ere!” They were given a Lewis gun, a thing with a magazine that looked like a round plate on top. They were able to try it out in a valley near Thorpe Cloud. I went with them and saw them fire it. I was about seven at the time.

I remember the Princess Royal coming to the hospital. My father organised a guard of honour and the Home Guard stood proudly to attention with their rifles while she inspected them. My father walked behind her. Before the war the hospital had been a nursing home, but during the war the blue uniforms and red ties of the wounded soldiers convalescing there became a familiar sight in the village. I saw my first sound film at the hospital. We had a 16 mm projector at home, but not with sound so this was a great novelty and cause of excitement. I was told the sound track was down the side of the film and I imagined it to have a groove and a needle, rather like a gramophone! The film was set in World War I and was called “Q ships”. These ships were harmless looking little boats masquerading as fishing boats that crept alongside German subs, but when the subs surfaced to attack them, the wooden sides of the boats opened up to attack the subs!

Sergeant Salt was very active in Parwich during the war. He was very keen on the blackout. Once he knocked on our door and reprimanded us for having a light showing. “Where?” asked my father. “Well, sir, you just come out ‘ere and I’ll show you”; whereupon my father was instructed to kneel down on the grass with his eye level with the ground. “Now do you see,” said the Sergeant? “You can see a light under the hem of that curtain.”

Mrs. Graham (mother of Miss Graham) at the Post Office was a formidable lady. We thought she was a witch. As children, we were very scared of her. When you went in to buy a stamp you had to be sure and leave the door open so that you could run out if you needed to.

I used to love watching the blacksmith; Mr. Bradbury was his name. He had an old fashioned bellows with a cow’s horn on the end of the lever. I loved the smell when the shoe was put on the horse’s hoof and it sizzled. Eventually the smithying didn’t pay enough and he went to work at Friden.

My father (Edward Halliday) later worked for S.O.E. (Special Operations Executive). He designed and had built a headquarters at Milton Bryan(t) close to Bletchley Park, where he ran a secret service radio station monitoring German radio and putting over our own black propaganda. My father is mentioned in a book called “Black Boomerang” written by Sefton Delmer who reported that unfortunately all records from Milton Bryan had been destroyed, but one day I decided to look in my father’s old tin trunk under the stairs, and there they were his wartime papers and logbooks. They are now in the Imperial War Museum.

I once went to look for my father’s headquarters with a friend, and found some brick buildings, which he thought was it. Each building had its own generator house. However, the location didn’t seem right: but as we passed an overgrown lane on the way home, I had a sudden flash of recognition, so we turned round and drove up the lane, and there it was, the building designed and built by my father, now being used by the boy scouts. Recently there has been a video made about it and a memorial plaque has been unveiled at the site. Milton Bryan, or Bryant as we called it, is on the outskirts of the Woburn Abbey estate.

In the tin trunk containing my father’s papers were many caricatures of his colleagues. He was, of course, an artist, a painter, but also interested in architecture and industrial design.

He designed the interior of the buildings in Dolphin Square. After the war, he wanted to go back to painting but felt there would be no money for portrait paintings. Instead he proposed to take a job at the Glasgow School of Art, but my mother did not wish to move there. Then he got his first commission from the Drapers’ Company to paint the young Princess Elizabeth. After that, he was in great demand. Once the princess became Queen everyone needed a portrait of her, so she’d say “Oh get Edward Halliday to do a version of his portrait of me!” So he did this, changing the backgrounds to suit the commission, Government House in Rhodesia say, followed by the Town Hall of an English town.

Before the war my father had done a lot of broadcasting, taking part in programmes on art and industrial design. Then it was realised that he had a good steady voice, so he was sent to report on everything from mining disasters to ship launchings and royal weddings. He was also involved in very early pre-war television. In fact he was the first person to take live cameras to Burlington House (the Royal Academy) on Varnishing Day, which caused a lot of excitement at the time.

After the war, my father was back in early TV, doing live interviews and arts programmes, but also becoming ‘the voice’ in the Television Newsreel, which went on for five or six years. On Coronation Day an hour long newsreel was produced, and the commentary for the last reel was being recorded as the penultimate one went out on air!

Copyright © 2004 Gill Radcliffe

THE JOHNSON FAMILY

ames Johnson, born around 1805 at Mercaston near Brailsford, left home when his widower father remarried. Walking with his pack tied to a stick, he came to a junction near Sandybrook Hall where, not knowing which way to go, he threw his stick into the air and it landed pointing in the direction of Parwich, so that is where he went. In Parwich he became apprenticed to a shoemaker. He married Ann (from Ford in Staffordshire) who was born around 1807, and they lived at Staines Cottage where they proceeded to have six children. According to the census of 1851, Hannah, age 17, was a teacher. William, age 15, worked at home [as a shoemaker presumably] while Thomas, (age 13), Georgia (age 10) and Sampson (age 5) were all scholars, which left Anne, the baby, who was one year old.

By 1871 the family had moved to Dam Head [not known which house this is] and James Johnson was a shoemaker and farmer with fifty acres of land. By 1881 they were in Dam Farm where James was farming sixty acres – no mention of shoemaking now. On the census of 1881, Matilda, James Johnson’s granddaughter, the eldest daughter of his son, William, was also staying at Dam Farm. Ann (his wife) is no longer mentioned on the census. Presumably, she died sometime between 1871 and 1881. In the 1891 census, none of the family is mentioned.

William Johnson, son of James and Ann, was born in Parwich in 1836. When first married, he lived in the ‘One up, One down’ cottage which used to be by the shop. Prior to that, he farmed with his father at Dam Farm, and later at Pool Close, Ashbourne. He married Mary Ann Day from Stanton, and they had six children: Matilda (born 1875 in Parwich), Ellen (Nellie) born 1877 (possibly in Parwich?) Sarah (born 1879), William (born 1881), Mary (born 1883) and Annie (born 1885). Ellen (Nellie) was Audrey Davies’s grandmother. Their mother, Mary Ann, the eldest child of her family, went into service age 9, when her mother died.

In addition to the information relating specifically to Parwich, Audrey has a copy of a letter written by relatives in Ashbourne which suggests inviting Mary, her mother, to live in Ashbourne in order to attend school there. The letter is from Audrey’s Great Aunt Mary to her sister (Audrey’s grandmother Ellen, known as Nellie) and it gives an interesting picture of the time.

Pool Close,

Ashbourne,

31st Dec. 1913

My dear Nellie and Ted,

I am so glad you liked the cakes and piano [?]; we should have liked to have sent you something for yourself too but we have all been so busy this last 3 months and have been so short of cash lately we really couldn’t get anything this time. I left Sarah’s [her sister] on Christmas Eve and came home again. Her servant came on Monday morning and yesterday they sent for them to fetch the baby home. I went down to Ashbourne last night to take her the baby’s basket back which I had been lining for her; it is one Tilly bought for her for Xmas and I was so surprised to find the baby had come home. She is such a little thing but they say she is strong. Sarah and Blanche Sellers and Mrs. Thacker all went in a Taxi to fetch her. She was very cross when I was in, the journey had upset her.

Tom wanted to pay me for doing the work for them, but of course I couldn’t take money from them so they bought me a chain bracelet and Annie [the youngest sister] a little pendant for the extra work she had had. I was very sorry for them to buy me that because they have been so very nasty with mother and it made her very poorly to be so upset. They never ask her or any of us to peep inside their house; and Tom has not been up for 3 months or more now. Sarah is quite well enough to come up if she would but she takes long walks in the opposite direction; it is very unkind of her and mother does feel it; Sarah does get such a lot like Aunt Pam and she will soon be as fat if she goes on. She looks so well and Tom is getting stout too, but they are such a lazy pair you would be surprised at them if you could see them.

Tom won’t come here because he is afraid of meeting Charlie Wass (my boy); he is very angry with me for going with him, he says he couldn’t possibly think of walking down the street with him or any of the family. He is such a nice boy, I am sure you and Ted would like him; he is a lot like Ted both in ways and looks. He came nearly every day last week, because he had holiday and he comes every Sunday to Tea. You know he is a Plumber like his father, I expect you remember him.

We went to George’s wedding, Annie, Willie, and me; it was such a lively affair. Annie and I stay[ed] at Fauld the night before and I went straight to Church with George, but Willie came on the wedding morning to Shaws. We all stayed that night at Shaws. I was to have been a bridesmaid but thought I should not be able to leave Sarah so had to refuse. Millicent Webster took my place. They all looked very nice; the Bride wore a cream serge dress and wreath and veil and the bridesmaids had grey dresses and black velvet hats. George gave Mary a gold bangle with 3 diamonds in it and her sister Millicent, gold chain bracelets. They had such a lot of beautiful presents, about 90 they say and there would be quite 50 people at the wedding.

Charlie Adams came to the wedding; it is the first time we have met for nearly 4 years. He was very sulky and of course I couldn’t take any notice of him now. He was drinking like a fish all the day; every one was disgusted with him. Annie had a young man to see her for Xmas do you know. Arthur Shaw (George’s wife’s brother); he is about my age. He stayed from Tuesday to Friday and now this morning she had such a lovely card for the New Year from him. Willie had Bertha here for tea on Xmas day and Charlie came so we all had someone.

Mother says it would be nice for Mary [Audrey Davies’s mother] to come here for a year or so and go to school at Ashbourne; it would be a change for her and she would learn a lot more and she would like it all so much. If you would let her come we would fetch her and you could bring Willie yourself anytime. Thank you for the coupons, we are still saving them, but we have the tins; they have red coupons in them and you know you can’t mix them.

The fowls at home have never layed since October but we do get a few from the Cote. They are 8 for 1/- [one shilling] at Ashbourne. You will get tired of reading this twaddle so I will wish you all a very happy and prosperous New year from all, and our best love and remain

Your loving sister

Mary

PS I should like to come and see you so please say Mary can come and then I could fetch her.

Above William Johnson (bottom) and his wife Mary Ann Day (top)

William & Mary Ann’s Children

Standing: Matilda & Sarah

Middle: Mary, Ellen (Nellie) & William

Front: Annie

Audrey Davies’s grandmother, Ellen [the daughter of William and Mary Ann], was employed as a lady’s maid by Mrs. Turnbull of Sandybrook Hall. The letters which passed between them after Ellen had left her service to get married show a close bond of affection between mistress and employee. In contrast, a letter to Ellen’s sister, also employed by her, is terse and to the point.

Sandybrook Hall

Ashbourne

Sept 24.1906

My dear Ellen,

I am enclosing you £5 as perhaps a little money will be more useful to you in sterling housekeeping than any other present though I had intended to give you a little ornament – I send with it every good wish for your happiness and I give it you in special recognition of all your kind services to me personally during the time you were with us – I hope you will always think of me as your friend and let me know of your joys which I trust will be many and of your sorrows if you ever have any – May they be few!

I am giving you a copy of dear Monica’s book because I think you may like to have it – (not to put with your presents) – You will like some of the verses written by her when a child.

I enclose a card which should have accompanied the tea service – and with very best wishes in which I know Mr. Turnbull most heartily joins.

I am your friend

Phyllis A. Turnbull

I hope I shall just see you tomorrow to bid you goodbye.

The book was a poetry book, “A Short Day’s Work” by Monica Peveril Turnbull, one of Mrs. Turnbull’s daughters who died in a fire. The book was published privately. Audrey Davies still owns her grandmother’s copy. The tea service was Crown Derby.

Sandybrook Hall

Ashbourne

Oct 30. 1906

My dear Ellen,

I was very glad to hear from you and to know you are so comfortably settled. I miss you very much but it is nice to feel you are happy in a home of your own. I hope some day you will be near us again.

Mr. Turnbull has had a bad finger but I think it is now getting well – and Krospie [?] came home yesterday with a very deep cut in his paw which made him feel very much depressed but he is more cheerful today. We have had deluges of rain and I should think all the springs are full to overflowing.

We met your father the other morning walking about and looking more like his own self than I have seen him for a long time. But I am afraid the constant changes of weather try him a good deal.

I hope you like the church where you are and find the services a help and comfort to you. Mary left us on the 24th and at present I have Maud Hardy who lives at Mappleton – but I am expecting a parlor maid on the 6th of November.

Poor little Mattie has not begun [to sing?] again yet – I suspect he misses the bright days of summer as I do. I hope you will let me hear from you often and believe me your true friend always,

Phyllis Turnbull

Sandybrook Hall

Ashbourne

Dec 30. 1907

My dear Ellen,

I am sending you two little toys for the Baby and a little white shawl. I am so glad she is getting on so well – I was very glad to hear from you. We have had a very quiet Xmas. The weather is now very cold – freezing winds – so I am afraid real winter has set in at last. I have not seen your people lately but hope to go and see your Mother before long. I do not think there is much news to tell you – Miss D. [?] is engaged to be married but she is not going to be married for a year or so.

I trust this New Year will be a very happy one for you dear Ellen and that all you love will prosper and mend. I hope when spring comes you will be here again and that we shall meet.

Believe me ever your faithful friend

Phyllis A. Turnbull

To Ellen’s eldest sister Mrs. Turnbull writes:

Sandybrook Hall

Ashbourne

July 15. 1914

Matilda

I shall be glad if you can return here either tomorrow night or what will do quite equally well – pretty early on Friday morning. We expect to go away again next Tuesday and I want you to do a few things for me in the next day or two. You can have the few days at home next week. I have to entertain a large party on Friday afternoon at the Hall Hotel and shall want you to help me dress.

I hope you are having a nice holiday.

Please thank Ellen for her letter.

From Mrs. Turnbull

As Audrey Davies points out, it is interesting to note the difference in the way Mrs. Turnbull addresses Ellen and her sister Matilda. In 1914 Matilda would have been 39 years old and Ellen, 37. Mary, another younger sister, also worked at Sandybrook Hall.

Also of interest is the notice of Ellen’s wedding in the local paper

The Ashbourne Telegraph Friday October 5th, 1906

WEDDING A very pretty wedding was solemnized at the Parish Church on Wednesday (September 26th), between Miss Ellen (Nellie) Johnson, second daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Johnson, Pool Close, Ashbourne, to Mr. Samuel Edward Griffiths of The Thorns, Whalley Range, Manchester, youngest son of Mr. and Mrs. Griffiths, Hissington, near Churchstoke, Montgomeryshire. The bride was attired in a white embroidered muslin dress, and picture hat to match, and carried a shower bouquet of choice white flowers. She was attended by her sisters Misses Mary and Annie Johnson, who wore dresses of cream alpaca, and cream hats …. Both bride and bridegroom were the recipients of a large number of useful presents.

Copyright © 2004 Audrey Davies and Gillian Radcliffe

On the publication of “Voices: Women of a White Peak Village”

I must tell you how I enjoyed the wonderful book, “Voices: Women of a White Peak Village”. I could not put it down. It was two o’clock when I went to bed with such lovely memories of the lovely people I knew for sixty years. My husband, Frank, brought me here when my son was a fortnight old, in 1944, from London and the ‘Blitz’. So you can imagine how I felt, a city girl, coming into Parwich. My dear Frank told me there were Marks and Spencers, Woolworths, the Co-Op etc: I suppose he was worried that I would not come here otherwise! We didn’t know where we were going to live or anything, but we ended up living with his grandma, Mrs. Steeples, and Mrs. Mary Ellen Allsopp, his mother. Frank was demobbed in 1946 and in 1947 we got our own house, No. 3, Sycamore Cottages, built especially for servicemen. I used to look out of the window of my mother-in-law’s house every day to watch them go up, brick by brick, and then came the big freeze of 1947, 7 weeks I think. I cried buckets. I can’t describe the feelings I had the day we moved in, running hot water, a proper toilet and even a bathroom. I think it was one of the happiest days of my life, and that was only the beginning. I could go on forever. Thank you!

Copyright © 2004 Anne Steeples

The inquest of Peter Brailsford at the Crown Inn in 1867

The article in our last Newsletter No. 16 p.16-17 on “Richard Greatorex & the Crown Inn prompted Linda Brailsford to send us the following information. Ed.

I read with interest your item about the Crown Inn in July’s Newsletter. I know that in May 1867 the ‘landlady’ was Mrs. Esther Nadin as I have a copy from the Derby Mercury about an inquest held on 29th May 1867 at the Crown Inn Parwich:

District News – Parwich

“On the 29th ult. an inquest was held at Mrs. Esther Naidin’s, Crown Inn, Parwich, before Ambrose Owen Brooks, Esq. Coroner, on the body of Peter Brailsford Labourer, who died suddenly the 28th ult.—The evidence of John Gould showed that the deceased was employed by Mr. Thos. Gould of Hawkeslow. About 10 o’clock on the morning in question the deceased was throwing manure into a cart, he stooped down to tie his boot, when he fell forward. Witness lifted him up, and he immediately died in his arms. Dr. Twigg was sent for but could render no assistance.—Verdict “Died suddenly from natural causes, by the visitation of God”.”

The death certificate reveals Peter Brailsford was 53 years old when he died and includes no new information other than “Information received from A O Brooks Deputy Coroner for the Hundreds of High & Low Peak in the County Of Derby. Residence Bakewell Derbyshire. Inquest held 29th May 1867.”

The deceased was my husband’s great great great grandfather, he had young children (two of them born in Parwich, Peter in approximately 1863 and Selina who was christened at St. Peter’s on 2nd April 1865). Peter senior was born in Biggin near Hulland but his wife Eliza Ensor was born and lived at times in Ballidon. One of Peter’s grandchildren Eliza was also christened at Parwich on 27th May 1877.

It would appear that the Gould family from Hawkeslow were kind and compassionate employers as on the 1871 census Charles Brailsford, aged 21, is employed as an indoor servant and on the 1881 census Selina Brailsford, then aged 18, is employed as a general servant.

Family History is a fascinating subject if slightly ‘spooky’ as my husband who was born in Ashbourne had no knowledge of his Parwich/Ballidon connections until recently. In 1964 I moved to Pike Hall from Derby with my parents and brother and in 1967 we moved to Parwich. I met my husband in Parwich although we were married at Mickleover as my parents moved there in 1977. I discovered approximately 18 months ago that my grandparents had a great grandmother in common, Hannah Hall who was born in Ballidon and christened at Bradbourne in 1804.

So all those years ago we returned to ‘our roots’ and probably went to school, whist drives and garden parties with distant relatives. It really is a small world!

Copyright © 2004 Linda J Brailsford

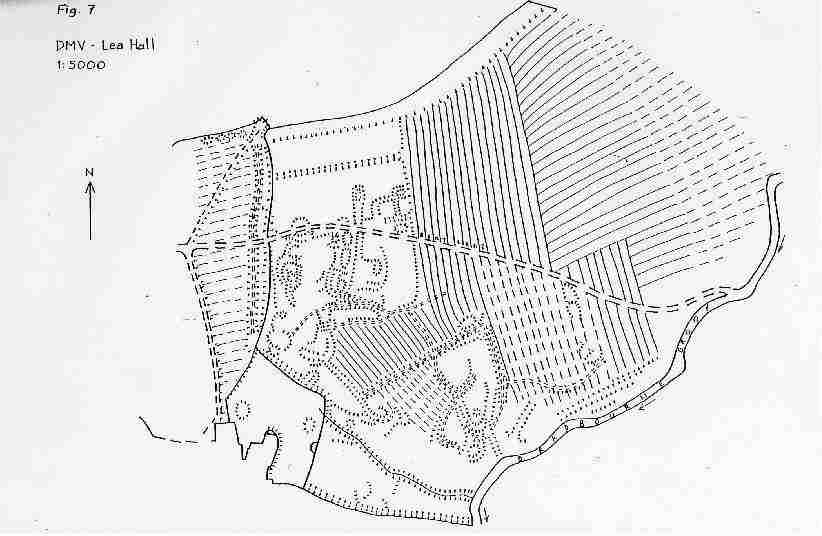

LEA HALL: an extract from the “South Peak Archeological Survey”

This is the smallest parish surveyed, situated on the eastern edge of the survey area and bounded on the west by Tissington, on the south by Fenny Bentley, and on the north by Parwich and Ballidon. It lies on the Upper Carboniferous sandstones and shales with a maximum elevation of 215 meters, graduating quite steeply down to the Bradbourne and Bentley Brooks on its east and southern border and more gently to the Bletch Brook on its northern. Its boundary with Tissington lies along two un-named streams, one of which runs north out of Bent Dumble down to Bletch Brook, the other of which runs south through Chough Riddins and into Bentley brook. Only one road passes through: that known as Bent Lane, stretching from Tissington to the ford across Bradbourne Brook at Bradbourne Mill, where it joining the B5056. The B5056 is the Fenny Bentley to Haddon Turnpike, authorized in 1811, and Bent Lane may have been constructed to join up with it since it bisects the ridge and furrow and does not appear to follow the known medieval routes.

The parish comprises only three farms: Gorsehill in the north, Lea Cottage in the centre and Lea Hall in the south. There is no eponymous settlement today, the parish taking its name from the deserted village of Lea. The bulk of the village site is thought to lie underneath the present-day complex of Lea Cottage and Lea Hall farms. It does not seem to have been extensive and was probably of minor importance compared with the surrounding villages of Tissington, Bradbourne and Parwich. Whether it is as old as these other settlements is also uncertain. There is no reference in Domesday (1086), but, as the Domesday compilers often assessed groups of settlements as a single fiscal unit nothing is necessarily proved by its omission. The earliest written reference to the site is to be found in the Cartulary of Dunstable Priory of 1215, when it is called simply Le Lie. In 1265 it was recorded as Lea Juxta Bradeburn, and, in 1546, as Le(e) iuxta Tissington.

The name Lee or Lea is a Normanised version of OE leah, meaning land cleared from woodland for cultivation. In Derbyshire there are 149 leah placenames apparently originating after the Conquest, so it is probable that this settlement was begun sometime in the economic and agricultural boom of the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. The modern name Lea Hall seems to derive from the fieldname Cornlehale, listed in a document of circa 1300 and implying an area cleared for growing corn. Another slightly earlier fieldname, Bothehalis, is suggestive of one or a group of meaner dwellings that might have been the origins of the settlement, since the name means ‘the place of the bothy’ the word deriving from Old Danish both. It must be remembered here that fieldnames tend to incorporate descriptive elements that have been handed down into dialect and may have long outlasted the original language. The use of a Viking loan-word is not an indication here that Danes started the settlement.

The earthworks associated with the hamlet concentrate in the large field to the east of the farm buildings on Lea Cottage farm. There is no readily discernible pattern of tofts; merely a haphazard system of banked enclosures of varying sizes, sunken trackways, and, here and there, possible building platforms. Of particular interest is a line of three, possibly four rectangular depressions backing onto a truncated holloway with an isolated platform at its northern limit. These are reminiscent of the sunken floors often associated with early Saxon buildings, though it is unlikely they are of this date. Also worthy of note is a crossroads of holloways in the centre of this field,, south of Bent Lane. One of these tracks, that running east-west, stops abruptly in the middle of nowhere. The point where it ends is probably a gateway into the medieval field, with the holloway itself being the route down from the village along which the plough was brought. Another very obvious holloway runs behind western boundary of this same field, parallel with it and leading into the complex at its southern end, while joining with a track on Gorsehill Farm at its northern end. Here it heads away in the direction of either Ballidon or Bradbourne, and may well be one of the two routes recorded in the thirteenth century: Balideneswei or Churchwei. This would depend upon which church, Bradbourne or Tissington, the locals were expected to use.

The modern track bypasses this holloway, which is likely to have been the main route in and out of the village. It forms the butt of a series of parallel strips running east-west to the west of the village site, comprising shallow ridge and furrow divided at roughly equal intervals by more prominent ridges. As these back onto the modern farm complex under which it is thought the main part of the village lay, it is possible that these are crofts once belonging to individual homesteads; though for crofts to have been ploughed is not common, except where it occurred after desertion. In the far west these crofts end on a bank and ditch which lies on the same north-south line as a series of boundary walls. This possibly marks the edge of the medieval field system of Lea, though the parish now extends to a line beyond, running south from the brook that flows out of Bent Dumble. Interestingly, at the point where it meets this parish boundary, Bent Lane makes a right-angled detour to kick round land at present belonging to Lea Cottage. This is probably the result of a land dispute at the time the current boundary was established. It does not however, appear to be the derivation of the name Bent Lane. The element bent is found in several names immediately local and is a reference to a type of rough grass used for pasture. The ridge and furrow associated with the deserted village seems to demonstrate a classic three-field system. It is best preserved in the modern fields north, east and east of the settlement, but is fainter south of the Lea Hall – Lea Cottage complex. The usual patchwork appearance of medieval field systems is apparent, though the slope of the land dictates that much of the ridge and furrow runs down to the Bletch, Bradbourne and Bentley valleys. A wide headland seems to form the division between an inner, central field surrounding the village, and a field to the north, half of which is now Gorsehill Farm. The lynchet forming it flanks the southern boundary of Gorsehill and also the holloway noted above. It appears to continue westward in a line that joins with Bent Lane, where this enters the Lea field system just east of the parish boundary.

Traces of north-south banking may be the remains of the boundary with Tissington, as suggested above, but the division between the central and southern field is not immediately obvious unless it is along the line of a spring in the field immediately south of Lea Hall farm. As already noted, banks between strips can be seen in the field west of the farm-complex, and these are also discernible in the field at the south-west corner of Gorsehill. Little trace of ridge and furrow is visible in the extreme south of the parish, though there is some evidence of ploughing through lyncheting with a series of possible strip lynchets. Field boundaries also seem to preserve a pre-Parliamentary landscape, though it should be recognized that some field-shapes are based on topography. As to when and why Lea was abandoned, these are questions largely outside the scope of the survey. Wolsey’s depopulation Commission of 1518 heard two cases of depopulation regarding Lea – a fact which has led to the assumption that the village was enclosed and abandoned at about this time, but mentions were still being made in documents into the last quarter of the sixteenth century, and The Lea is drawn on the maps of Derbyshire executed by Saxton and Speed in 1577 and 1610. If anyone was left living at that time, it seems unlikely that they were ploughing. The ridge and furrow associated with the settlement is much fainter than that on adjacent Tissington; therefore it is possible the area was enclosed for pasture after population levels fell too low to be economically viable.

Evidence of pre-Medieval activity is lacking for Lea Hall, and the only feature found by the survey to which a definite medieval or post-medieval date cannot be assigned is a group of possible platforms in a steep field next to Bradbourne Brook at its southern end. A track winds through and leads to a dilapidated arched bridge across the brook and up onto the Fenny Bentley Haddon turnpike. Doubtless this is a packhorse bridge of post-medieval date; however, a document of circa 1400 mentions in the context of Lea an area known as Brigge Medewe. If this is the same, then presumably there was once an older bridge on the same site. Yet there is no trace of the trackway once out of the area of earthworks, unless it is coming in from the north across the current field boundary. As to the context of the platforms, these do not seem to be industrial, being on the shale but with no evidence of quarrying. Substantial evidence of shale quarrying can be seen at the northern edge of the parish, and the remains bear little resemblance. Possibly, if this was an area given over to sheep in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the earthworks are associated with the washing and shipping of wool. This, however, is only a very tentative suggestion for which the authors have no hard evidence.

This plan give an good idea of the complex nature of the field patterns, house platforms and trackways that make up the ‘lost parish’ of Lea Hall.

A Walk through Lea Hall to Woodeaves Farm

On an evening in July the history society organised a walk that started in Parwich and traced its way through Lea Hall (see above) and on to Eileen Simm’s farm at Woodeaves (see information in issue no. 19). Despite what was a rather overcast, though warm evening, a group of 11 members were able to view what is one of many shrunken settlements in the area.

The ridge that runs west of Bradbourne Brook is comparatively isolated though it must have once been a busy route with its numerous trackways. Lea Hall itself, with its complex of ancient field patterns and house platforms, gives tantalising hints of this past. The section from the South Peak Archaeological Survey quoted above provides an excellent summary of what can still be seen at Lea Hall. This medieval village now only has three farms (Lea Hall, Lea Cottage and Gorsehill), with Lea Hall probably being on the site of the original manor house. Also on the walk was Rosie Ball who was brought up at Gorsehill Farm.

After Lea Hall we continued along one of the comparatively unused footpaths that follows the ridge through Choughriddins. That this is a deserted and strangely wild terrain was apparent when even Eileen lost her way only a few hundred yards from home. As dusk fell we finally made our way into Woodeaves Farm. What Eileen lacked in her sense of direction she amply made up for with her excellent hospitality, food and drink. Thanks Eileen, truly an evening to remember.

A view from behind Lea Hall showing the extent of the modern farm.

The old road that lead from Lea Hall to Bradbourne. Now hardly more than a dip, this photograph shows how it lines up with the modern road in the middle distance.

Now an old barn this building seem likely to have been the 17th century farmstead.

Copyright © 2004 by Rob Francis

Leave a comment